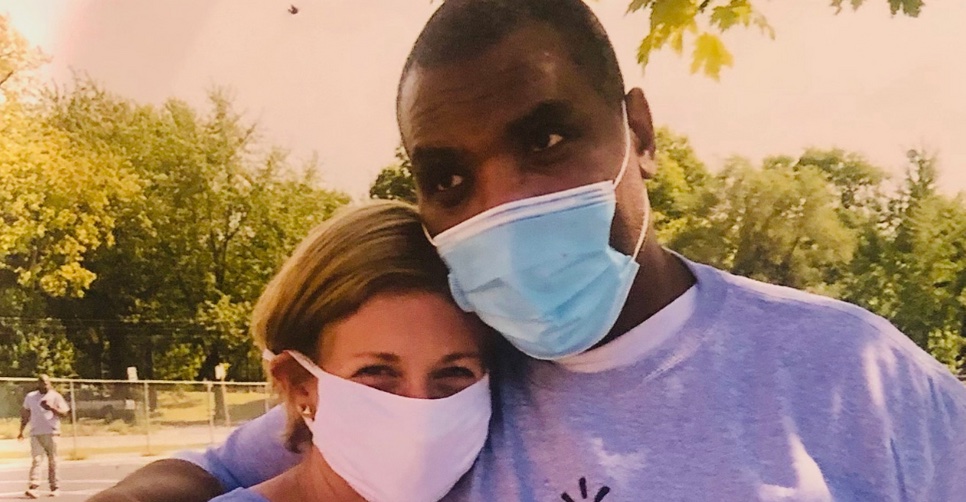

Three Questions: Q&A with Jennifer Soble, executive director, Illinois Prison Project, and Renaldo Hudson, education director, Illinois Prison Project

Founded in 2019, the Illinois Prison Project (IPP) works for a more sensible and humane prison system in Illinois by advocating for and on behalf of thousands of people who are needlessly incarcerated.

Project Funded by Illinois Humanities

“Stateville Calling” is an hour-long film created in partnership with Scrappers Film Group to identify and examine the injustices and issues that face elderly people who are confined in prisons. With IH assistance, the IPP toured this film virtually throughout southern Illinois, featuring the Second Church of Christ in Danville, Ill., and the Center for Empowerment and Justice in Carbondale, Ill.

Q1: How do you see the arts/culture/humanities as being essential?

Jennifer Soble: Part of our mission is to help people who have no experience in the criminal legal system understand the ways in which we are actively harming everyone around us — others in our community, parents, children, grandparents — through our regressive and racist criminal legal system and through our system of mass incarceration. The data is overwhelming and undeniable. But even if you show people numbers all day long, they will not resonate in the way that telling peoples’ stories resonates. And so for us, the arts and humanities are crucial to helping people understand on an emotional level the harm that mass incarceration is inflicting on us all. It’s through the arts we help people feel the criminal legal system directly, and why they care about it and why they need to act to change it.

Q2: What is the most important thing people should know about your work?

JS: The most important thing for people to know about our work is that we are bringing hope to thousands of people who literally had no lifeline before we existed. The overwhelming majority of people who are imprisoned right now have no access to release no matter how rehabilitated they are, no matter how wonderful they are, no matter how sick they are, or whether they are disabled. They have no way to come home. Our court systems are designed to protect convictions and sentences as they were imposed. The legal system has done nothing but throw up obstacles for review in Illinois and in other places. Our work is singularly designed to elevate and shine a light on the humanity of all those folks who are in prison right now, to literally start carving pathways ways out of prison so that these really wonderful and deserving folks have a shot at returning to their families.

Renaldo Hudson: I would add that I was in the Illinois Department of Corrections for 37 years. I spent 13 on Illinois death row. In 1983, I was a functioning illiterate. By the time I was 19, I had been shot in the chest by my brother, witnessed my aunt murdered, my cousin murdered, my twin murdered, and in a drugged-out state, I took a man’s life. But when you look at your life, you want to believe you are more than the worst thing you ever did. So after many years of incarceration, I learned to read and write. I educated myself. I became an activist in prison. But there was no release for me. There was nothing available that said ‘Renaldo, after you put your life in order, the system will now look at you as someone at least under consideration.’ Right? That does not exist. I filed multiple clemencies. But it was only when the Illinois Prison Project stepped into my life, and filed a clemency, and actually told my story, that my humanity came forward. Because somebody looked at me and said, ‘We won’t just look at your crime, we’re going to look at the potential in your humanity.’ There’s no other organization doing that work, and that’s why I love the fact that I’m now a part of the IPP and not just a client. I’m able to breathe today because of this work.

Q3: Who makes your work possible?

JS: We wouldn’t exist without the support and trust and faith of our foundations and donors, who have created the space and freedom for this project, which really was a fever dream of mine one day. I’m immensely grateful for the broad community of supporters who recognize the need for this work and have moved mountains to make sure we have the resources we need to build and grow. But I think the people who have really made this work possible are the thousands of people and their families in the Department of Corrections who have put their faith and trust in us, to not only represent them in legal proceedings and in advocacy with the Department of Corrections, but who have worked with us to tell their own stories. It’s not my story that anyone wants to hear, it’s Renaldo’s story, and Tewkunzi Green’s story, and its Vickie Quinn’s story, it’s Bryant Harvey’s story, it’s the story of our clients, both current former, that will help the community and our public officials and our lawmakers understand why backing criminal justice reform is so desperately needed, and so it is the folks who have been willing to share their story — people who are currently or formerly incarcerated – that make this work not only possible but worth doing.

RH: I am learning each time I share my story. People reach out to us, and say, ‘Wow, I had no way of knowing this is going on, that there is no parole in Illinois.’ It’s amazing — and I lived with it, like knowing there is no parole, every day. I lived with people who had out dates, that were more hopeless than me. And so when you talk about breathing hope, imagine the population of aging citizens who happen to be incarcerated, and are thinking ‘Hey, maybe people are starting to hear our stories. So thank you, Renaldo, thank you, Sherman, and all the different people who are sharing their stories. And what people don’t know is that we are sharing our stories, while still trying to swim out of our trauma. Because many of us suffer from compound trauma. Incarceration is very traumatic, because you’re conditioned to think you’re less than a human. You’re constantly told, ‘You don’t matter. And that’s why society threw you away.’

Q4: Anything else you’d like to add?

RH: It’s like I’ve been frozen — like I was a caveman, if you will — who was thrown out. And I’m like, look at all this stuff that is going on. If I could say anything, I’d say to people, ‘Open your doors so we can come share our stories — open up your churches, your schools, all the different venues, so we can bring our stories in, and people can see our humanity. To see that we’re just men and women who made bad decisions. So if I could say anything, I would say to the world stage, there are thousands of people in prison who don’t have relief. We have to share the story of how tragic that is. I celebrate my freedom — I can breathe. I was crying the other day, because I was thawing out. I don’t have to be afraid of saying something. In prison you are punished for saying, ‘I am a human being. Don’t treat me like this. It’s wrong that you have me locked in this cell, with no hope, no prospects of relief.’ But you better not say nothing.

DOWNLOAD THE FULL SPOTLIGHT ON THE ILLINOIS PRISON PROJECT

More about the Illinois Prison Project:

IllinoisPrisonProject.org | @ILPrisonProject | @ILPrisonProject | @ILPrisonProject

The Illinois Humanities Grantee Partner Spotlight

Bi-monthly Illinois Humanities highlights the work of our Community Grants program partners through our “Grantee Spotlight.” It shines the light on our grantee partner’s work, offering details about the organization and the funded project, as well as a Q&A with a team member at the organization. More: ILHumanities.org/Spotlight

About Illinois Humanities

Illinois Humanities, the Illinois affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, is a statewide nonprofit organization that activates the humanities through free public programs, grants, and educational opportunities that foster reflection, spark conversation, build community and strengthen civic engagement. We provide free, high-quality humanities experiences throughout Illinois, particularly for communities of color, individuals living on low incomes, counties and towns in rural areas, small arts and cultural organizations, and communities highly impacted by mass incarceration. Founded in 1974, Illinois Humanities is supported by state, federal, and private funds.

Learn more at ilhumanities.org and on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn @ILHumanities.