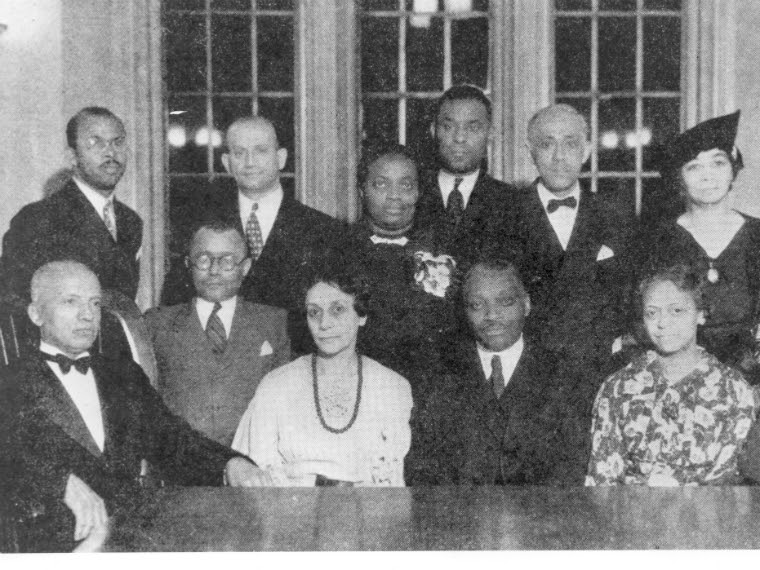

Image: Committee in charge of the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, 1935. Dr. Carter G. Woodson is sitting to the far left. Chicago Public Library Photograph

February 23, 2021

Friends,

Illinois has a special connection to Carter G. Woodson’s invention of Black History Month. Woodson, who studied history at the University of Chicago and was a vibrant historian of Chicago’s south side, was determined to transform how people thought about Black history. He launched “Negro History Week” (the forebearer of Black History Month) at the Wabash Street YMCA in Bronzeville, in Chicago, in 1926, to coincide with the February birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Five decades later, in conjunction with the country’s bicentennial, his idea become a nationally-recognized month-long commemoration.

Imagine if Illinois had a state mandate to design, encourage, and promote education about the African slave trade, slavery in America, the many contributions of Black people in building our country? What if this commitment was bolstered by workshops, institutes, teacher trainings, and memorialization of events concerning the enslavement of African Americans, their descendants, and their struggles for freedom, liberty, and equality? What might our shared understanding of Black history be like? Might it extend well beyond the month of February?

We came close to having just such an investment when, in 2005, the Illinois General Assembly enacted the Amistad Commission to recommend changes to state curriculum and textbook content.That commission did not achieve its aspirations. However, in 2019, the New York Times published The 1619 Project with the goal of “reframing the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” That recasting, bolstered by the Pulitzer Center’s curriculum project, has transformed and enriched the way many people think about the history of the United States. I count myself amongst them.

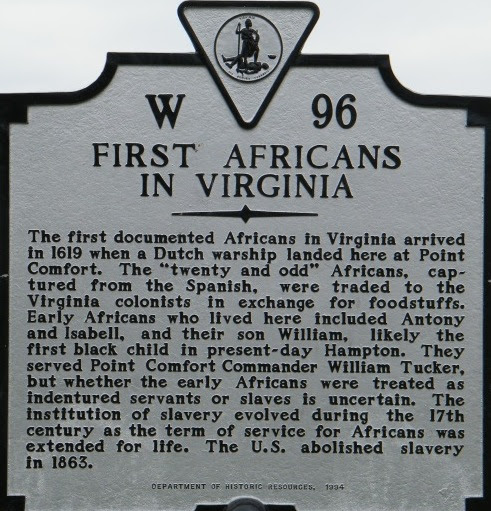

Image: “This Day in History” by Michael Knepler.

Earlier this month, in an Op-Ed for the New York Times, “Isn’t 400 Years Enough?“, former Illinois Humanities Board member, now President of Rutgers University, Jonathan Holloway, wrote, “The failure to appreciate Black history leaves our nation incomplete.” Serious consideration of the history of our country through the lens of the experiences of Black people, he writes, raises fundamental questions: “What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be a citizen? What does it mean to be civilized?”

Earlier today Illinois Humanities announced the commission of 14 artists and humanists who will create new works illuminating the experiences of people and communities impacted by mass incarceration. It is fitting we announce these commissions during Black History Month; mass incarceration is a direct descendant of American slavery.

The works being created offer vibrant opportunities for precisely the kind of “assessment about actions versus ideals” Holloway calls for in his Op-Ed. To highlight just a few,

- Alexandra Antoine and Brandon Wyatt will create Our Agreements, a 42-card deck with questions and prompts about what we perceive as our values, roles, and regulations. They will also post screen-prints of prompts in vacant buildings and on billboards in Galesburg.

- Tara Betts and David Weathersby will create Unbarred Poetics, short videos featuring Illinois poets describing experiences with the carceral state, paired with writing prompts and resources.

- Mitchell S. Jackson’s Survivor Files will build on the work in his acclaimed book Survival Math. Jackson will create portraits (both still and moving) of Illinois-based individuals alongside narratives of some of the things they’ve struggled to survive.

A number of the projects are being created by currently or formerly incarcerated individuals and several are being shaped by individuals whose families are directly impacted by the carceral system.

At Illinois Humanities we see these commissions as part of an effort by a broad and diverse community to create a more complete narrative. The historical record is incomplete, complex, and contradictory; the work of history is to find untold stories, illuminate biases, create new narratives, and wrestle with incongruities. Black History Month, The 1619 Project, and perhaps, the works created by Envisioning Justice Commissions, help us consider Holloway’s questions with the seriousness they deserve – What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be a citizen? Perhaps along the way we’ll develop a collective historical perspective that will better equip us to design the country we want, need, and deserve.

In the weeks and months ahead we’ll be sharing news about the commissions and letting you know how you can see them and be part of the conversations they’re designed to spark. In the meantime we’ve got a number of programs and opportunities we’d love for you to spread the word about:

- March 1st is our deadline for Activate History grants and May 15th is the second of three 2021 deadlines to apply for a Community Grant.

- On March 10th we’ll be sharing a major report, “On Wisdom and Vision,” about the impact of COVID-19 on public humanities organizations and, on the impact these organizations are having across the state in mitigating the terrible effects of the pandemic. You can register HERE for the virtual breakfast program.

- Our statewide Gwendolyn Brooks Youth Poetry call for submissions from young people grades K-12 is open through May 31.

- Finally, if you were one of the hundreds of people who watched one of our People, Places, Power programs featuring Gallatin, Fulton, or Cook Counties, we’d love for you to take a SURVEY and let us know your thoughts.

Stay well, stay warm.

Gabrielle Lyon, Executive Director