November 23, 2020

Dear Friends,

As the holdiay season begins, we are at an intersection of celebration and sorrow that is forcing us, on a daily basis, to ask questions about ourselves and about each other.

COVID-19 is devastating communities in rural, suburban, and urban Illinois. We find ourselves wondering why we respond one way to public health recommendations while our neighbors respond differently. In the wake of the 2020 election—no matter who we voted for—we are asking, “What does it mean that so many people voted for the other candidate? How could they do that?”

These questions create dualities that put us in opposition to one another; they feel like magnetic poles repelling us from one another. We are asked to dismiss what’s unintelligible, resist what is unacceptable, and sustain the familiar.

In a powerful session during last week’s National Humanities Conference entitled “Humanities 2030,” which included Illinois Humanities’ own Director of Teaching and Learning, Rebecca Amato, panelists were asked what could enable people to imagine the future. One response: speculative fiction.

Speculative fiction posits other worlds and other ways of being. Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, 1993, is an example. So is Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, and Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves, 2017. The utopian, dystopian, science fiction, fantasy and Afro-futuristic worlds of speculative fiction are as myriad and diverse as the writers who have crafted them.

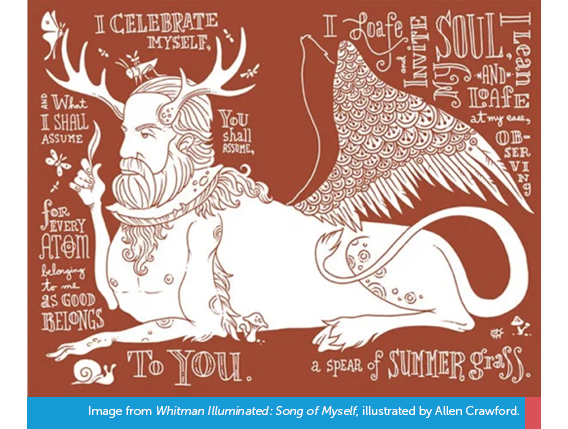

Perhaps Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is also a kind of speculative fiction. It’s a work I’ve been thinking of often this fall. The poem was written at a time when the nation was convulsing with contradictions about identity: how to (or whether to) reconcile with a legacy rooted in slavery; how to (or whether to) integrate or welcome immigrants; how to (or whether to) make it easier for advantage to accumulate versus protect the vulnerable amongst us.

Whitman was educated in public libraries, through debate societies, by going to the theater. He wrote for “the people,” the “everyman,” the “worker.” He self-published Leaves of Grass on July 4, 1855, of which “Song of Myself” was an early component.

It opens,

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” [1]

We share a common humanity.

He writes:

“The sickness of one of my folks or of myself, or ill-doing or

loss or lack of money, or depressions or exaltations,

Battles, the horrors of fratricidal war, the fever of doubtful news, the fitful events;

These come to me days and nights and go from me again,

But they are not the Me myself.” [4]

And, in doing so, asks us to remember ourselves and reminds us that we are not these things. He answers his own final question…

“Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.).” [51]

Whitman’s belief in the power and majesty of each of us resided in a powerful embrace of ambiguity. Despite maps that paint our geography in broad brush strokes of red or blue, no county in Illinois voted 100% for either Donald Trump or Joe Biden. These are complex places. We are a multitudinous people.

We need questions that encourage speculation; questions that expand us rather than limit us.

The theme for our November 11th Envisioning Justice Rapid Response program was RE-VISION. It was anchored in the kinds of questions the humanities so adeptly provide:

How can the past shape the future without limiting its radical possibilities?

In the future, who advocates for the people to bloom, flourish, and grow into liberation?

If freedom has a sound, what does it sound like?

These are questions that ask something of us individually while simultaneously helping us to ask questions as a community.

Imagine a country in which every single person was equipped to ask questions like the ones Johnnetta Cole asked during the National Humanities Conference:

With whom do we share this earth?

How did we come to share this earth?

What are the ways that the stories of each of the world’s people enrich my story?

How did this complex thing get this way?

Would it be better if it were reassembled in a different way?

What might it be like to live in that place? How would it feel? What might be possible?

Maybe we could find common ground and perchance consider the possibility that common ground may not be the right goal;

Maybe we could find our way through differences via dialogue;

Maybe our state’s multitudes and contradictions could enable possibility and strength.

Maybe we would sing our present moment as a struggle about the kind of society we long to create.

At Illinois Humanities we are working thoughtfully to ask questions that help us move away from duality and towards diversity and multiplicity. Thanks to your help and encouragement, we are continuing to find ways to be our best selves as an organization passionately committed to activating the humanities to foster reflection, spark conversation, build community, and strengthen civic engagement.

I’m looking forward to sharing information next month about some very special opportunities– including a fun new Illinois Humanities game that will arrive just in time for the holidays.

On behalf of the staff and board at Illinois Humanities, please stay well.

Yours in community,

Gabrielle Lyon, Executive Director

PS

I strongly encourage you to check out our Odyssey Project instructor Hilary Strang’s lecture on speculative fiction, and to read this powerful interview with Nicole Bond, an alumnus of The Odyssey Project, in which she describes how the humanities changed her life.

Activating the Humanities

Illinois Humanities, the Illinois affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, is a statewide nonprofit organization that activates the humanities through free public programs, grants, and educational opportunities that foster reflection, spark conversation, build community and strengthen civic engagement. We provide free, high-quality humanities experiences throughout Illinois, particularly for Black, Indigenous, and communities of color, individuals living on low incomes, counties and towns in rural areas, small arts and cultural organizations, and communities highly impacted by mass incarceration.

Founded in 1974, Illinois Humanities is supported by state, federal, and private funds.

Learn more at ilhumanities.org and on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn @ILHumanities.