“We stood about in the Sampson yard, not close together as people huddle in the face of a great sorrow. We stood a few feet apart, as the law required,” writes Ruby Berkley Goodwin in It’s Good to Be Black, her memoir of her formative years in the small town of Du Quoin, located “in the heart of the coal belt of southern Illinois.”

Goodwin, who later became an accomplished actor, poet, and journalist, had gathered with fellow African American residents of Du Quoin to mourn one of their own, Freeman Sampson, who had died under a collapsed coal ledge. Goodwin and her neighbors sought togetherness as best they could while taking precautions necessitated by the influenza pandemic of 1918-19, when “schools were closed and the people who ventured on the streets were grotesquely masked with protective coverings of medicated gauze.”

A little more than a century later, during another pandemic that has necessitated precautions and limited people’s ability to gather, another African American resident of Du Quoin, Nicholas Tate, stood at an intersection near the yard where Freeman Sampson’s friends and relatives had congregated. Like them, Tate was seeking togetherness following the loss of an African American man, George Floyd, who had died under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. He held a sign reading, “ONE HONK TO ACKNOWLEDGE BLACK LIVES MATTER.”

“Some people drove by, they started honking, and before you know it, people that were honking were pulling over in the parking lot of the grocery store, and they were coming and joining us,” Tate explained in an article by Molly Parker in the May 31 edition of The Southern Illinoisan. “We had probably 20 people out there with signs and stuff helping with the protest.”

Parker’s article continues, “Though the protests drawing the most attention are in major cities, Du Quoin Mayor Guy Alongi said that small demonstrations like this are a reminder that people are concerned about issues of fairness and justice in rural towns, too.”

Alongi – whose Italian ancestors, like Ruby Berkley Goodwin’s African American family, were drawn to Du Quoin by the mining industry in the early 20th century – commented, “There are times when nonviolent protests can be very effective, and this is the time for everybody to have those conversations in their local communities.”

In recent weeks, I’ve had the privilege of listening to and participating in such conversations with representatives of various communities in Illinois, including rural communities, urban communities, and the public humanities community. Those conversations have reinforced my belief in four interrelated propositions:

1) Sustained dialogue between urban and rural Illinoisans is crucial.

2) Historical memory influences how we interpret and respond to events in the present.

3) Public humanities practitioners and organizations can facilitate rural-urban dialogue and constructive reflection upon historical memory.

4) In doing so, public humanities practitioners and organizations can contribute to the pursuit of a more just future for Illinois communities.

I’m grateful for this opportunity to share some personal reflections-in-progress on those four propositions, for whatever they might be worth. Because those propositions are intertwined, my reflections-in-progress on them are similarly interconnected. Furthermore, my reflections-in-progress really are just that, so I hope you’ll think of what follows as a rough draft on which I’ll welcome feedback – or, better still, as part of one of those conversations to which Mayor Alongi referred.

I was raised only about 35 miles west of Du Quoin, just outside Chester, a community of similar size. Several members of my family, including one who is a local police officer, live in Du Quoin, so I’ve visited there often.

I’ve also visited neighborhoods on the South and West sides of Chicago, the city in which I was based during my first four and a half years as an Illinois Humanities program manager (prior to the 2017 opening of our southwestern Illinois office in Edwardsville, where I now live).

In listening to what residents of those urban neighborhoods, most of them people of color, said during discussions facilitated by Illinois Humanities, I was struck by the extent to which many of their comments – especially their observations about challenges and obstacles facing their communities – resembled remarks that I’d often heard in places like Du Quoin and Chester.

I began to pay closer attention to cultural similarities and differences between urban and rural Illinois communities. Increasingly, I became convinced that urban and rural Illinoisans have more in common than they typically realize.

It also seemed to me that they sometimes honestly misunderstand the reasons for many of the significant contrasts between them. Furthermore, it appeared to me that better communication between rural and urban Illinoisans – especially if it were to improve both their recognition of their similarities and their comprehension of their differences – could help to mitigate some of the persistent problems confronting our state.

For that reason, several of my Illinois Humanities co-workers and I, in cooperation with the Covey Group and other partners throughout Illinois, initiated a discussion-oriented program series called The Country and the City: Common Ground in the Prairie State? in 2018.

One event in that series, “Local Law Enforcement & Community Relations,” took place in February 2019 at the African American Resource Center at Booker, located in an area of Rockford where police had shot several civilians in recent years. Drawing upon a scholarly article about the cultural dimensions of law enforcement in rural communities and an essay by James Baldwin entitled “Fifth Avenue, Uptown,” the discussion identified a wide variety of factors that can influence the relationship between a community and its police force, whether for better or for worse.

As a result of that program, we met Carla Redd, an assistant deputy chief with the Rockford Police Department, and Jerry Suits, the sheriff of Pope County. Both are natives of the communities in which they work, which form a study in contrasts. Rockford, near Illinois’s northern boundary, is the state’s largest city outside the Chicago metropolitan area. Pope County, along the Ohio River in southeastern Illinois, is the most sparsely populated county in the state. Chief Redd and Sheriff Suits insightfully compared their perspectives in a radio segment that we produced in collaboration with WNIJ FM in DeKalb and WSIU FM in Carbondale.

The discussion between Chief Redd and Sheriff Suits and the conversations that occurred during our The Country and the City event in Rockford indicated that the ways in which rural communities and urban communities tend to experience policing are substantially similar in some respects, yet substantially different in others. Those discussions suggested to me that many urban and rural Illinoisans have limited knowledge of one another’s experiences of policing. They also suggested to me that increasing that knowledge might be a step toward improving the cultural dynamics between them and developing law enforcement policies that could accommodate the needs and aspirations of both.

Likewise, the observations that I’ve heard from rural and urban Illinoisans in the aftermath of the horrific deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of law enforcement personnel indicate that there are both significant commonalities and significant contrasts between the ways in which they tend to experience policing. Based on their comments, I’m inclined to believe that their familiarity with those commonalities and contrasts is limited in many cases and that improving their mutual understanding might benefit both.

Many of my family members and longtime friends from rural southern Illinois, most of whom are white, gravitate toward relatively conservative views on social issues and tend to be supportive of law enforcement. It seems noteworthy to me that in my conversations with them and in their social media postings, none has attempted to justify the action that killed Floyd or to defend the officer responsible. There seems to be widespread agreement among them, as there is among my friends who live in urban settings, that the officer’s action was outrageously cruel and obviously unwarranted. They also seem to agree that the circumstances surrounding Taylor’s death were similarly profoundly disturbing.

My rural friends and relatives vary, however, in the degrees to which they believe that Floyd’s and Taylor’s deaths reflect a long-term pattern of racism and injustice. Many of them have denounced acts of violence directed at police officers by demonstrators, several of which have been fatal. They contend that the media hasn’t covered those incidents sufficiently. Many of them have also expressed dismay over the vandalism and looting that have accompanied protests in some cities.

Some are concerned about the possibility that violent reverberations from urban protests might reach their rural communities. A rural Illinoisan for whom I have the utmost respect and whom I’ll call “Steve” (not his real name) e-mailed me and other friends and relatives recently. Steve said that he considers George Floyd’s death an act of murder and believes that the Minnesota attorney general was right to charge the officer responsible for it with that crime. In that respect, he’s in agreement with the urban Illinoisans with whom I’ve been in contact.

Steve also discussed a report that was circulating among residents of his home county in southern Illinois, however. It was published by a website known for promoting false conspiracy theories. According to that report, a left-wing extremist group that has been inciting violence during protests in major cities was planning to begin attacking people and livestock in Steve’s county to send a message to rural America. Steve noted that the report had been discredited by the county sheriff’s department and is apparently “fake news,” but he said that he’s inclined to believe that scenarios like the one described in it are plausible, nevertheless. He encouraged readers of his message who live in rural settings to be prepared in case such attacks occur.

Steve’s message strikingly illustrated a difference of perspective between rural Illinoisans like himself and urban Illinoisans, many of whom have expressed the opposite concern: that right-wing extremist groups are using this crisis as an opportunity to harm inner-city communities. It reminded me of an observation made by author David Wong: from the viewpoint of many rural Americans, “trends always start in the cities – and not all of them are good. What rural Americans see on the news today is a sneak peek at their tomorrow.”

Wong made that comment in an essay called (perhaps unfortunately), “How Half of America Lost Its F***ing Mind.” That essay, published on Cracked.com shortly before the 2016 presidential election, includes a great deal of gratuitous profanity, vulgarity, and culturally insensitive language, which I don’t condone. Nonetheless, it also contains significant insights about rural-urban tensions, drawing upon Wong’s experience of growing up in a rural community in southeastern Illinois.

Wong says that white residents of his hometown tended to make a distinction between African Americans who lived nearby, especially those whom they knew personally, and African Americans who lived in cities. They considered the former to be fellow members of their community and usually treated them as neighbors, according to Wong, but they regarded the latter with suspicion and often made uncharitable overgeneralizations about them. He attributes that tendency to the fact that his white neighbors learned much of what they knew (or thought they knew) about urban African American life from pop culture or from news reports that provided little contextual information.

I imagine that long-established local traditions and historical memory also contributed to that tendency, whether Wong’s neighbors fully realized it or not. Such traditions and legacies often influence patterns of social relations in which we participate without our being entirely aware of them. That’s one reason why thoughtful exploration of historical memory as it relates to race is so important.

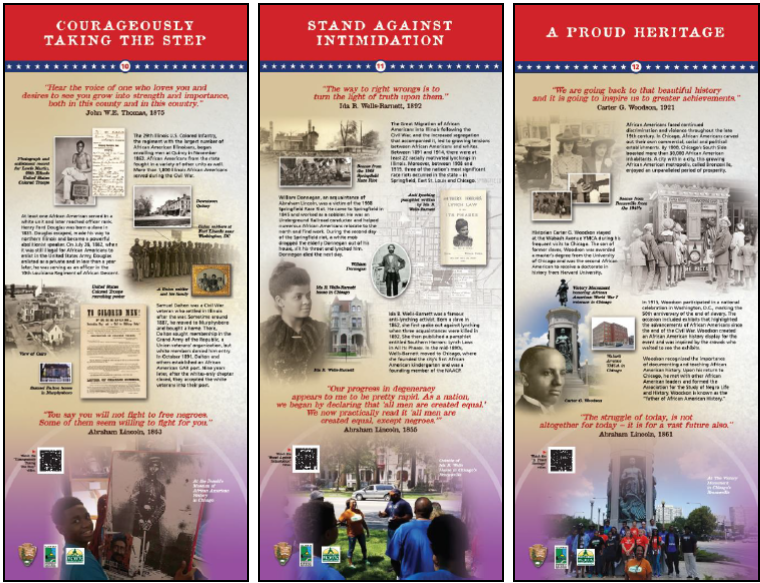

Members of the Lawrence County Historical Society, based near where Wong grew up, are conducting research on African American Civil War soldiers from Lawrence County. They’re examining not only the soldiers’ military activity but also the experiences that motivated them to serve and what they indicate about race relations in the region. They’re considering options for applying that research. On a broader geographic scale, the exhibition produced by the Illinois Freedom Project discusses various milestones in the pursuit of civil rights by African Americans over the course of our state’s history.

As those two public humanities projects illustrate, the history of policies regulating race relations in the southern third of Illinois during the 19th century and much of the 20th is complex and not easily categorized. In some ways, those policies resembled ones that were characteristic of the rural South. In others, they were similar to those typical of the urban North. For African Americans who experienced them, they were no less insulting or painful than those of either the South or the North, but they differed from both.

Ruby Berkley Goodwin contends that in early-20th-century Du Quoin, for example, “there were few penalties that could be traced directly to color,” and she describes relations among the ethnic groups represented there as being largely harmonious. On the other hand, she mentions that at least one local coal mine refused to hire African Americans, and she laments that the church built by her grandfather was destroyed by a fire that members of the congregation believed to be arson. Furthermore, several communities near Du Quoin were sundown towns – municipalities with ordinances prohibiting African Americans from being there between sunset and sunrise – or the sites of racial expulsions.

I’ve occasionally heard white Illinoisans argue that it’s unfair of African Americans to allow such injustices endured by their ancestors generations ago to influence their own perceptions of white people and predominantly white communities in the present. I would gently remind them that they often allow their own interpretations of their own present-day experiences to be influenced by historical memory – by their pride in the Revolutionary War veterans buried in a nearby cemetery, for instance, or by their identification with their German American ancestors who labored diligently on their farms and built the local Lutheran church.

I might also respectfully note that many of those German American ancestors weren’t spared from severe discrimination, themselves, especially during the two world wars. In fact, last month, the Illinois State Historical Society dedicated a marker memorializing the 1918 lynching of Robert Prager, a German American coal miner, in Collinsville.

Madison County, in which most of Collinsville is located and where I now live, has epitomized the complexity of race relations in the southern third of Illinois throughout its history. One of its most prominent early citizens, Colonel Benjamin Stephenson of Edwardsville, practiced slavery-in-all-but-name by coercing African Americans to become “indentured servants” with decades-long indentures. (Sadly, that practice wasn’t uncommon among influential Illinoisans in the early years of statehood, as this June 19 ProPublica article by Logan Jaffe explains.) The 1820 Colonel Benjamin Stephenson House thoughtfully interprets that history.

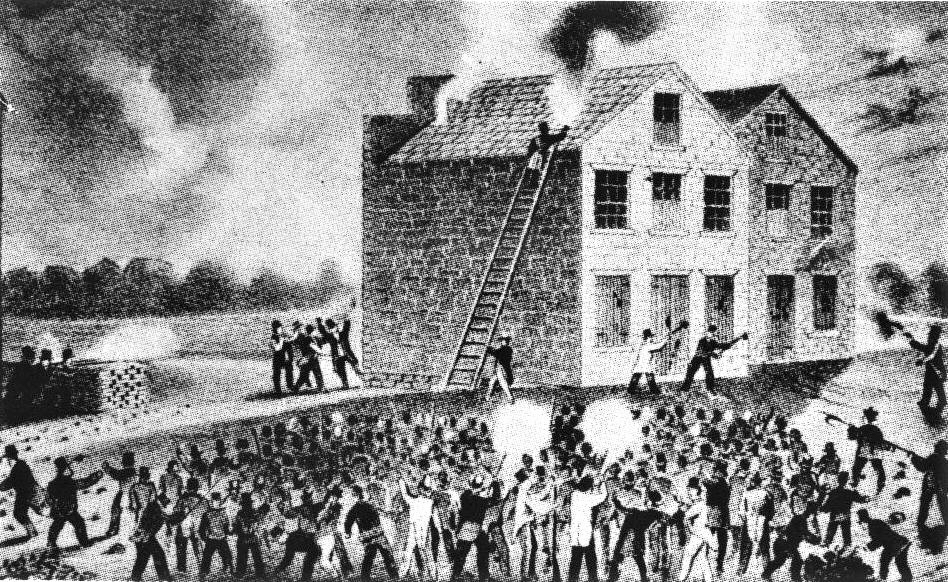

In contrast, the Reverend Elijah Parish Lovejoy of Alton published an anti-slavery newspaper – but he died while trying to prevent a mob from destroying his printing machinery in 1837, becoming the first known martyr to the freedom of the press in the United States.

On the grounds of the building that houses Illinois Humanities’ Edwardsville office, there’s another Illinois State Historical Society marker. It indicates the site of the courthouse where political foes of Governor Edward Coles convicted him in 1824 of illegally freeing people whom he previously kept enslaved. The building itself served as Edwardsville’s African American school prior to integration in the 1950s. It’s now called the Mannie Jackson Center for the Humanities, named for an alumnus of that school who achieved remarkable success in both business and sports and received our organization’s Public Humanities Award in 2018.

On Sunday, May 31, approximately 300 people added a paragraph to the history of race relations in Madison County by gathering in Edwardsville to protest the killing of George Floyd and systemic racism. They stood along North Main Street in front of the courthouse and the county administration building, where our next Museum on Main Street exhibition, Voices and Votes: Democracy in America, will be displayed next June. The same evening, the Edwardsville Police Department issued a statement denouncing police brutality and commending the demonstrators for protesting it nonviolently.

According to an article by Charles Bolinger published in the Edwardsville Intelligencer on June 3, Edwardsville mayor Hal Patton made the following remarks at a city council meeting two days after the protest: “As I watched the video in horror, I pleaded for that officer to get off him and for someone to help Mr. Floyd. It was a disgusting act of cowardice to put that amount of pressure on a man that was clearly immobilized on the ground and in handcuffs. I have no idea why that officer, and those who stood by and watched, were not arrested immediately upon seeing that tape. Had that happened in this city, the offenders would have been on their way to jail before you could rewind the tape! I clearly understand the civil outrage that followed. We are all outraged, and we should all demand justice for Mr. Floyd. That is why I was so pleased to see how our community responded with a large yet peaceful gathering of hundreds of people from different backgrounds and different generations.”

The mayor then announced the formation of two action groups, one focusing on equality of opportunity for people of color in Edwardsville, the other addressing fairness in policing and public safety.

We at Illinois Humanities fervently hope that these initiatives and others like them will prove to be steps along a sustained course toward a more just future for Illinois communities. By engaging rural and urban Illinoisans in constructive dialogue, by facilitating critical reflection upon historical memory, and by cooperating with valued partners across our great state, we will assist as best we can in the pursuit of that future.

A postscript: Since this essay was completed, additional protests have occurred in Edwardsville and Du Quoin, as well as other communities in the southern third of Illinois, including Anna, Benton, Carterville, Effingham, Granite City, Mount Vernon, Nashville, Pinckneyville, Sparta (where most of In the Heat of the Night, a movie in which race, policing, and rural-urban dynamics are significant themes, was filmed in 1966), and Staunton. For the most part, these protests have been locally organized, well-attended, and nonviolent. They have received substantial coverage in local and regional media, much of which is available online.